We held the final AGM for the Marine Biosecurity Toolbox project, after five years of intensive research and collaborations.

To clean or not to clean: views of boat owners in keeping boat hulls free of biofouling organisms

Researchers from the MANAGE AND RESPOND and ECONOMICS AND DECISION SUPPORT components of the Marine Biosecurity Toolbox programme have joined forces to work towards an understanding of what drives recreational boat owners in New Zealand. Social science and economic techniques are being combined to identify the factors that encourage or discourage hull cleaning behavior and to evaluate the preferences and values of boat owners when it comes to keeping their own hulls clean. This work is being supported by knowledgeable marine scientists and implemented in consultation with end users such as MPI and councils.

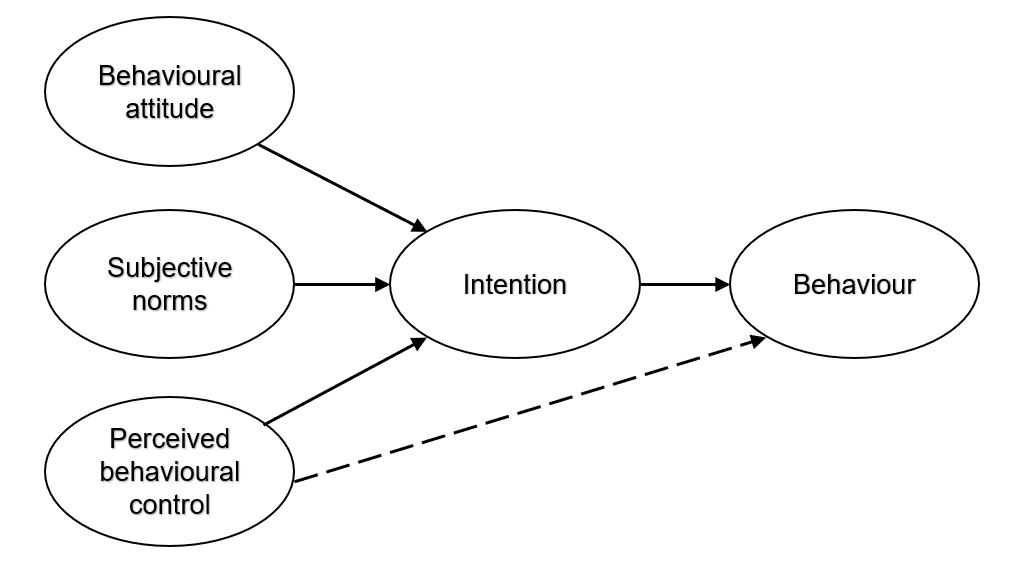

The social science theory of planned behavior predicts intentions to carry out behavior and elicits attitudes, subjective norms and perceived control (Figure 1). This theory is being used in combination with the economic valuation technique of ‘choice experiment’ allowing us to elicit boater preferences and estimate values based on choices made between competing policy options.

Figure 1. Diagram showing the key components of the theory of planned behavior.

A survey is in development to gain a good understanding of this marine biosecurity issue from a large sample of New Zealand boat owners. The first step towards understanding boaters’ views however, was a face-to-face focus group (attended by eight participants) that took place in Nelson in October, conducted by Richard Yao and Melissa Welsh from Scion along with Alaric McCarthy and Oliver Floerl from Cawthron Institute and Mark Newton of RMA Ecology (Figure 2). The focus group consisted of three sets of questions. The first set were descriptive questions, aimed at getting a feel for boat owner awareness of biofouling organisms, their current concerns and future aspirations, and the resources used to keep their vessel hulls clean. Open ended questions were used in the second section to help prompt the participants to discuss their views on the advantages and disadvantages and what might encourage them and other boaters to keep their hulls clean. The third set was cool-down questions, distributed to trial some of the developing questions for the national survey. In this article, we present the highlights of the responses to our first and third sets of questions. Results for the second set of questions will be reported in an upcoming article.

Figure 2. The hull cleanliness research team (From left to right: Alaric McCarthy, Oliver Floerl, Melissa Welsh, Richard Yao and Mark Newton).

Responses to descriptive questions

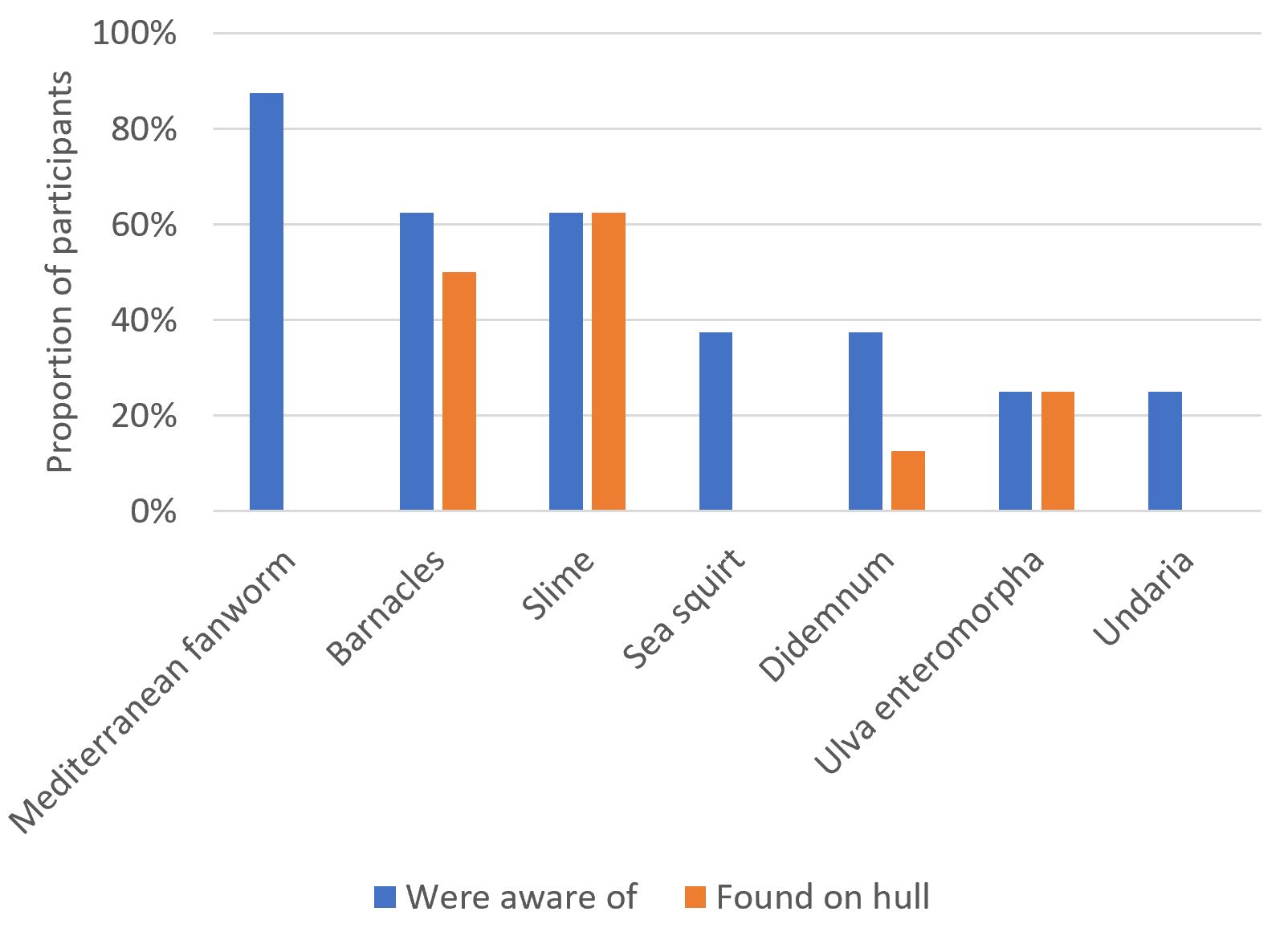

When asked to tell about biofouling species they were already aware of, participants identified four specific species and three broader types of biofouling organisms. Mediterranean fan worm (Sabella spallanzanii) was mentioned by all but one of the participants, while the more generic Slime and Barnacles were equally thought of by each of the five participants (Figure 3). Other organisms identified included sea squirts, specifically Didemnum, Ulva enteromorpha and Undaria. Of these organisms, slime was indicated as most found on participants’ boat hulls. Barnacles, Ulva and Didemnum had also been found.

Figure 3. Awareness of and presence of biofouling species on boat hulls.

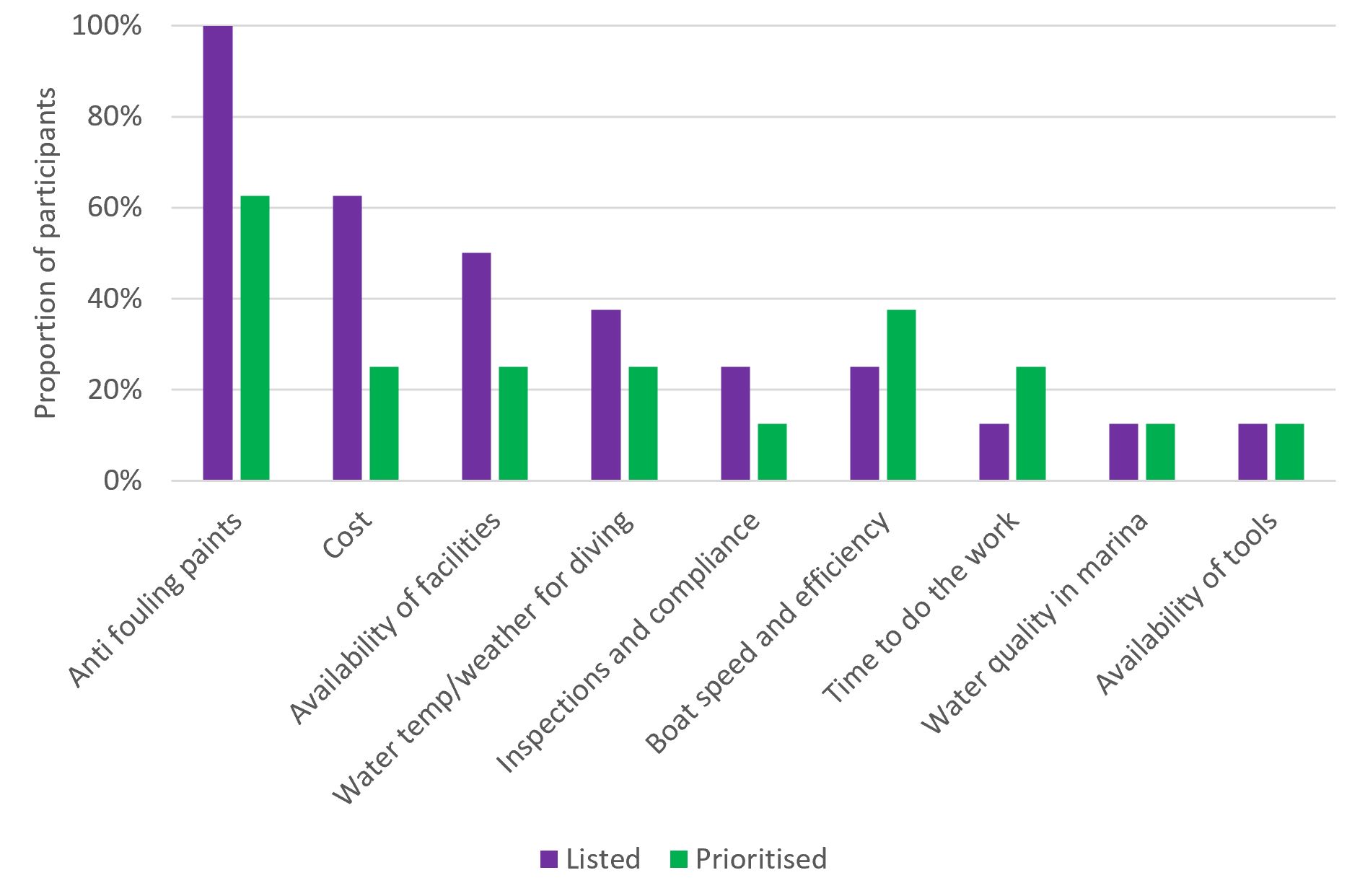

Participants were then asked to name some factors they considered to keep their hulls clean. The quality of antifouling paints was immediately of concern to everyone, it is important that the paint is effective and lasts for a reasonable amount of time (Figure 4). ‘Cost’ and ‘Availability of facilities’ were two other factors listed off the top of their heads. When asked which of the factors listed were of most concern, ‘Antifouling paint’ remained important, though it did not make everyone’s top three, and interestingly, boat speed and efficiency jumped up into second spot over cost and availability of facilities.

Figure 4. Factors listed and prioritised by participants in keeping boat hulls clean.

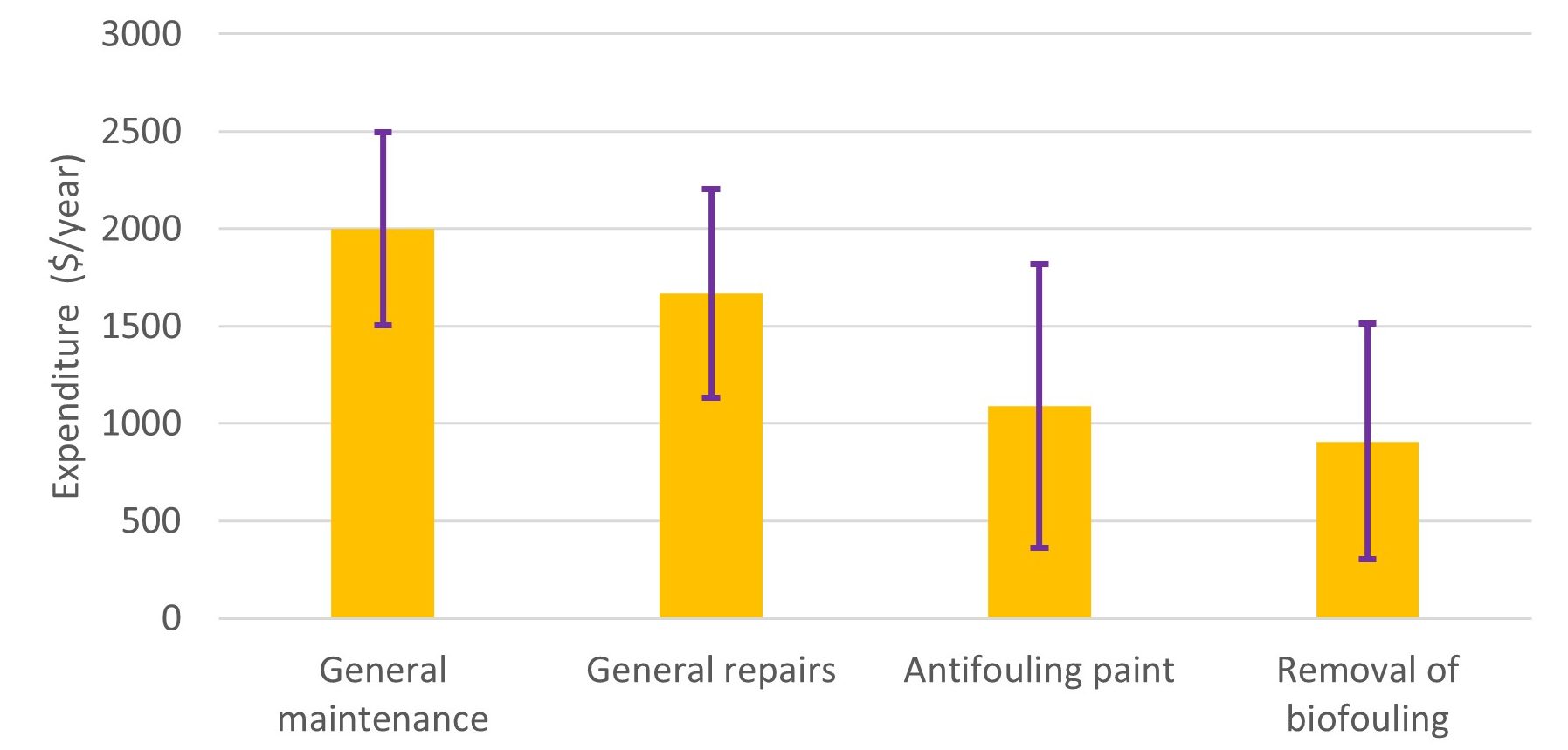

In terms of how boat owners typically spend money on their boats, removal of biofouling came out as the smallest expense, with participants spending an average of $906 per year (Figure 5). Slightly more money is spent on antifouling paint application, however other maintenance expenses such as work on the sails and other equipment is where most of their money goes. However, the combined average expenses of antifouling paint and biofouling removal is as high as the maintenance cost and greater than the general repairs, indicating that addressing the marine biosecurity issue is a significant increase in the cost of owning a recreational boat.

Figure 5. Average expenditure of each participant on boat maintenance and keeping hulls clean.

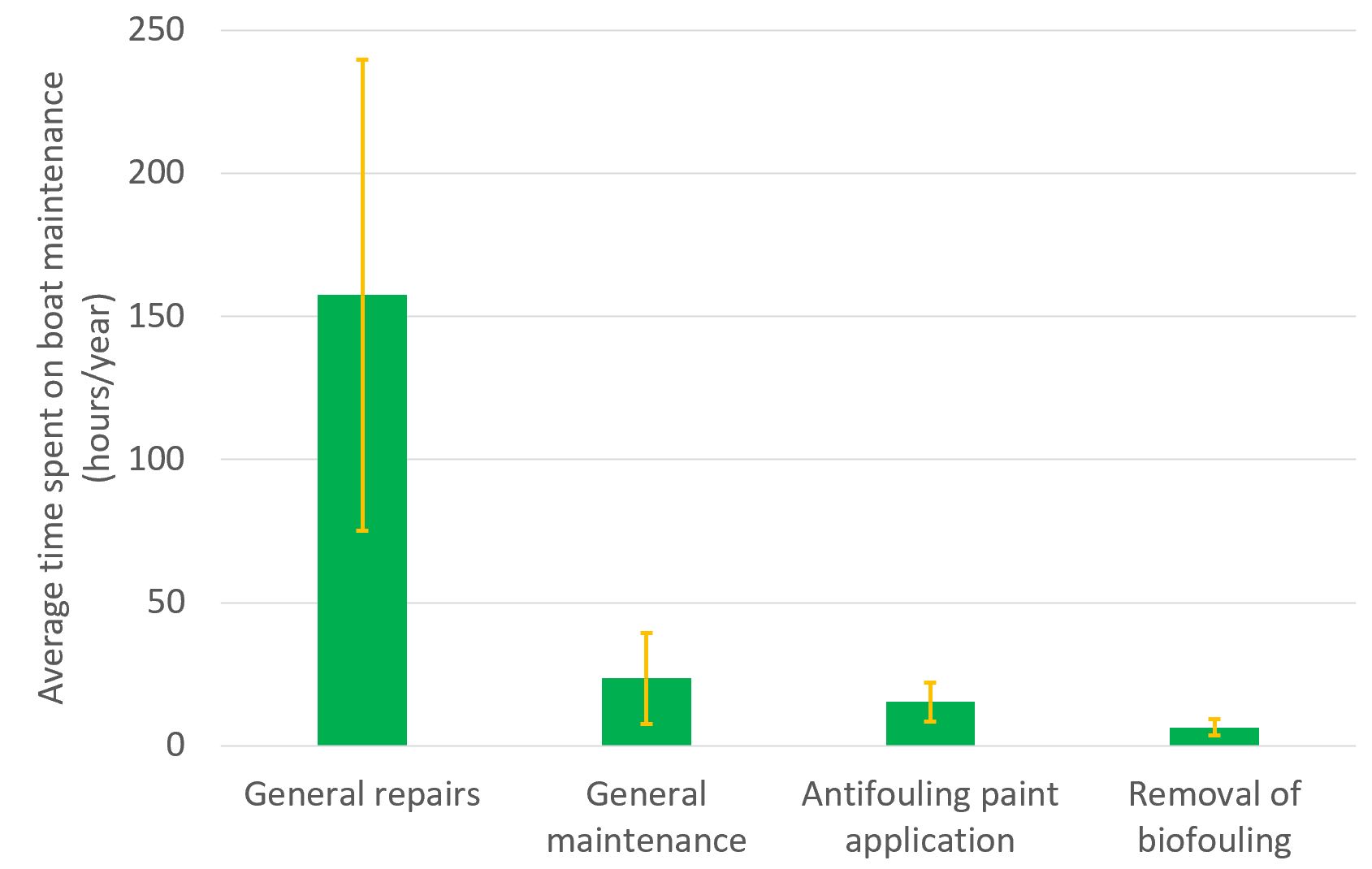

The average time spent on maintenance tasks by our participants followed a similar pattern to money, however, general repairs overtake general maintenance and significantly overshadows time spent on antifouling paint or biofouling removal in a typical year (Figure 6). In contrast to monetary expenses, the time spent addressing the biofouling issue accounts for a smaller proportion relative to general boat repairs.

Figure 6. Average time spent on boat maintenance and keeping hulls clean.

I was interested in the Nelson responses. They appear to not have such rigid control over where and when to haul out for cleaning/ antifouling.

In Auckland, it is no longer possible or allowed to beach a boat between tides to clean and paint the hull as we used to do. Diving / snorkelling to clean your hull on the mooring is fine with hard coatings _ in your questionnaire, you should include types of antifouling used on boats and if moored or in a marina berth. Fresh/storm water entry into a marina also reduces fouling meaning much less fouling.

I noticed that diving to remove barnacles from a hard coating anti fouling brought in clouds of snapper to eat them.

To lift out at Half Moon Bay Marina, clean, store for two nights and relaunch at end of November 2021 cost $698.00.

My wife and I did a thorough clean, sand, surface repair and touch up, a 4 litre coat of non ablative antifouling and topside waxing over two days with the paint, rollers and cleanup materials costing us $430.00, a total of $1128.00. We do this every six months to keep our hull clean and sailing efficiently.

I hope that the interrogating committee have some practical boating experience so that they understand and relate to the questions and responses.

Finally, I would like to ask what is going to be done to overcome the presence of all these “unwanted “species that are making their presence felt in our waters. It seems that all officials are doing is clicking their tongues in despair and putting unwanted infringements on boat owners as though they are the culprits. ie nothing! What eradication plans are being formulated to overcome the challenge?

Dear Tony

Many thanks for your reply – it is good to see that our updates are being read by NZ boaters and it seems that you are one of the many who take hull maintenance and biosecurity very seriously!

Thank you for your suggestions regarding the inclusion of specific questions in the questionnaire’ we will take this on board when we design the template. If you wish, we could include you into the ‘test group’ to whom we will make available a draft version of the questionnaire for feedback. Would that be of interest?

We are aware of the inability for boaters to use tidal grids or careen their boats on beaches for cleaning and coating renewal. This has been the case around many regions of NZ and also Australia. The primary concern is the release of antifouling coating fragments into the environment by abrasive cleaning methods, and the contamination of sediments and nearshore environments that can happen if hundreds or even thousands of boats are being cleaned that way.

As far as eradication and control of invasive marine species is concerned, we think you are right in that NZ has not been able to prevent the introduction and spread of several nuisance species that are now causing concern to NZ’s regulators, maritime industry, Māori and the general public. However, a lot of effort is being made to limit the spread and impacts of many of the species that have made it through the border. Many regional councils, or partnerships of several councils, are undertaking on-going surveillance and control programmes that attempt to reduce local infestations of invasive fanworms, tunicates and other species around many parts of NZ. Central government biosecurity agencies are undertaking a nationwide surveillance programme for unwanted marine pests, which has been going on since 2001 and given us a good handle on which species are where. Likewise, government and industry-led initiatives are underway to reduce biosecurity risk associated with commercial shipping and aquaculture operations.

Feel free to stay in touch via the contact email addresses or the generic contact form.

Best Wishes

Oli & Ana