We held the final AGM for the Marine Biosecurity Toolbox project, after five years of intensive research and collaborations.

Understanding habitat features of native mussel reefs

One of the major research objectives of the PROTECT theme is the development of artificial substrates to enhance populations of native species on coastal infrastructure. Once established, such populations can: (1) protect infrastructure from colonisation by marine pests, (2) provide ecosystem services, and (3) improve the connectivity of native populations around urbanised coastlines. A bottom-up approach is required to develop artificial surfaces that are attractive to native species and make them want to settle and stay for the long haul. Such surfaces can then be incorporated into coastal infrastructure, a process referred to as ‘ecological engineering’.

Our project is making a start using the endemic, green-lipped mussel (Perna canaliculus) – or kutai. This species occurs around New Zealand, provides important ecosystem services and is a valued kaimoana (seafood) species for many coastal iwi and hapū. Over the past decades, vast areas of mussel beds have been lost to coastal development and urbanisation. To date, no successful methods have been developed to create artificial surfaces that attract and retain mussels by virtue of their physical or chemical characteristics. Our programme will develop these novel artificial substrates that benefit native species, via an exciting collaboration between marine ecologists, material and engineering scientists, biochemists, kaitiaki and local government.

In March 2020, our project team from Cawthron, Scion, Patuharakeke Te Iwi Trust, Northland Regional Council and Macquarie University visited a number of mussel beds around Whangarei Harbour and identified a reef near Waipu, Northland, as a great field site to begin our research. The reef features green-lipped mussel populations and has traditionally been an important source of kaimoana for tangata whenua, and a taonga species. This site of cultural significance is a key focus of Patuharakeke mana moana committee’s restoration and management efforts.

Understanding the habitat requirements of kutai is a first step towards establishing new populations on coastal infrastructure.

Following a series of equipment trials, pilot experiments and method development exercises, the team returned to the Waipu mussel reef in mid-September, during spring tides, to undertake a detailed assessment of the ecology and physical habitat structure of the mussel bed. As a first step, we undertook an ecological survey of the reef and associated mussel bed. This involved the identification and quantification of mussels and the vast diversity of invertebrates and algae that live around and amongst them.

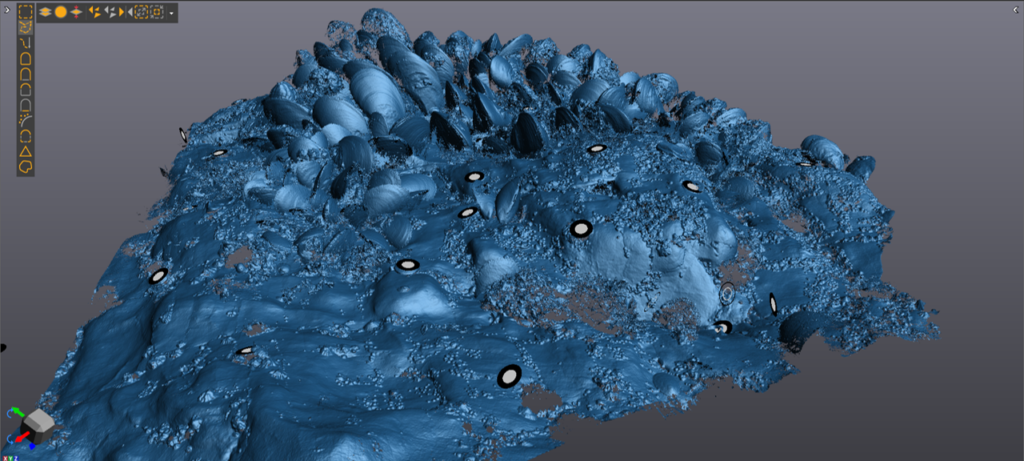

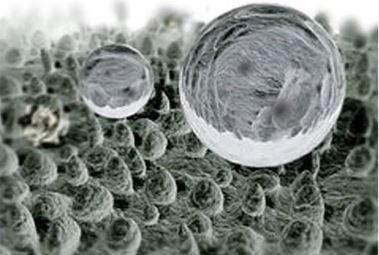

Our guiding question is: ‘What physical or chemical features make baby mussels want to live in a particular spot?” To find out we are using a portable high-resolution 3D scanner to create fine-scale digital models of mussel bed morphology. A mussel bed is a complex ‘matrix’ of organisms (mussels, algae, sessile and mobile invertebrates) and materials (shell hash, sand, pebbles, etc.). We started out by developing 3D scans of the larger mussels forming the upper (exposed) surface of the matrix. We then carefully removed these outer mussels, exposing the next ‘layer’ within the matrix, which turned out to be an aggregation of byssus threads, algae, barnacle shells and a myriad of other biogenic and geological features. This layer was scanned, and then removed – and so on, until we got to bare rock, which was also scanned to provide a model of the underlying mussel-bed topography. We also developed photogrammetry models of each scanned habitat layer. This provided us with image-based 3D models – which can provide colour and other useful information when combined with the scans.

Our scanner has a 10-micron resolution and is able to pick up tiny topographical features associated with mussels, other organisms and underlying rock. Here is Rob Whitton (Scion) scanning the outer layer of a mussel bed plot.

Our next step is to develop small physical models of these habitat layers using state-of-the-art 3D printing and additive manufacture technologies, and then conduct lab and field experiments to test the response of mussel larvae and juveniles to the range of physical features included in the models. This will take place over the coming 12 months and is only one aspect of the overall project – more information to follow as we progress.

To say we are pleased with the information collected during this first trip is an understatement. The approach we are using is a first for at least the Australasian region and we feel the collaborative planning and leg work of the past 6 months paid off in the best possible way. We will be posting updates on this project on a regular basis, so make sure you check back in or subscribe to our newsletter.

If you would like to find out more about this research please contact Oli Floerl, Paul South, Marie Joo Le Guen or Rob Whitton.

See below for a selection of images from this first scanning and sampling trip.

Examining the 3D structure of green-lipped mussel beds. Marie Joo Le Guen (Scion) and Paul South (Cawthron) remove a ‘habitat layer’ after scanning. Sumanth Ranganathan (Scion, on right) prepares a plot for photogrammetry.

Our 50-kg gazebo was not easy to get to the sampling location each day but provided critical shade for optimal scanner performance. Left to right: Kaeden Leonard (Northland Regional Council) and Paul South examining mussel bed biota, Oli Floerl (Cawthron) and Sumanth Ranganathan (Scion) recording data and making sure the gazebo doesn’t fly away, Rob Whitton (Scion) checking scanning files.

Now you see them, now you don’t! After the outer matrix (left) was scanned and characterized, all mussels were carefully removed to expose underlying layers of algae, shell hash, sessile invertebrates and rock features (right). These were then scanned, too.

It’s all in the detail! – A scan of the outermost surface of the mussel med matrix. 3D-printed models of outer and inner layers will be used in forthcoming ecological lab and field experiments.

Paul South (Cawthron) and Taryn Shirkey (Patuharakeke Te Iwi Trust) discussing the ecology of the local mussel beds.

Patuharakeke whānau and kaitiaki joined the fieldwork and provided insights on former and present distributions of mussels and other local kaimoana. Left to right: Tainui and Eddy Besselink, Juliane Chetham. Other participants included Ari Carrington, Shilane and James Shirkey, Reece Newton and Murray Smart.

[…] patterns of juvenile mussels on 3D printed habitat models developed by scientists at Scion from digital scans of mussel beds. Watch out for further updates as our experiments […]